Local Cops Aren’t Great at Solving Crime, FBI Data Say

Wed., Sept. 29: Everything you need to know about the feds’ new trove of crime info + no death penalty in Faith Hedgepeth case + Alamance Confederate monument suit moves ahead

+3 STORIES

1. DPD Cleared <25% of Its Violent Crime in 2020. RPD Was Worse.

The headline from the FBI’s data dump on Monday was that the national homicide rate jumped 29% from 2019 to 2020—which is, admittedly, a big deal. I’m surprised I’ve not yet seen any media coverage (perhaps I missed it), but the rise in North Carolina homicides was no less dramatic.

If you’re having trouble making out that image, North Carolina went from about 6.2 homicides per 100,000 people in 2019 to 8 homicides per 100,000 people last year—also a 29% increase.

The 377 law enforcement agencies—which cover 90% of the state’s population—that submitted homicide information to the National Incident-Based Reporting System, or NIBRS, reported 742 homicides last year compared with 602 in 2019.

The state’s violent crime rate went up by 10.7%, while the national rate increased by 4.6%.

It’s fashionable among some Back the Blue types to blame the uptick in violence on the Defund the Police movement …

“‘The distrust of police, the low morale among police, the fact that the police are being less proactive because they are legitimately worried about being backed up by their superiors’ were all contributing factors,” an Albuquerque Police Department consultant told The New York Times.

… but in most cities, cuts to police budgets were negligible or ephemeral. Seattle cut its police budget in part by shifting parking enforcement to another city department, for instance. Austin slashed its police budget by a third, but it did so by moving forensic sciences and support and victims’ services out of the police department.

In North Carolina, Asheville was the only town that cut its police budget in the last year—by $700,000, or about 3%. Raleigh, Charlotte, Greensboro, and Winston-Salem have all increased police funding.

Despite Durham shifting some vacant police positions to a new Community Safety Department, it didn’t reduce its allocation to DPD. Not yet, anyway.

While there’s no evidence linking Defund to more homicides, several studies suggest that adding police officers deters crime, at least in the short term. Of course, plenty of other research argues that proactive measures that don’t involve the justice system are more effective over the long run. I’ll leave that discussion for another day.

But one thing advocates of Durham’s reforms have told me over the last few months is that cops don’t stop murders or rape or assaults. They show up afterward and, we hope, catch the bad guys, which is why, advocates say, police should focus on violent crimes, not small stuff.

The deterrence debate aside, that strikes me as a reasonable enough point.

So when the trove of FBI data became available, I went looking to see how often the Raleigh and Durham police departments cleared violent crime cases.

First, let’s get some comparison data. Here are the FBI’s clearance-rate averages for all law enforcement agencies nationwide in 2019. (The graphic comes from Statista; the data comes from the FBI.)

As you can see—decades of Law & Orders be damned—your chances of getting away with a major crime in the United States aren’t too shabby, not that I’m suggesting you take any of these up as a hobby.

For a more relevant comparison, we’ll draw on cities with populations from 250,000 to 499,999, a category that captures both Raleigh and Durham.

Violent crime: 35.1%

Murder and nonnegligent manslaughter: 51.5%

Rape: 25.6%

Robbery: 23.8%

Aggravated assault: 41%

Again, not great.

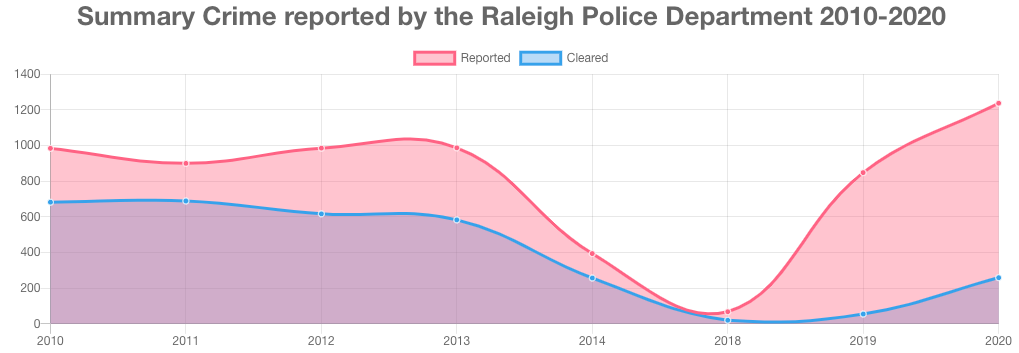

We’ll start in Raleigh, where—fair warning—the data are wonky:

Raleigh seems not to have reported anything to the feds between 2015 and 2017, and its crime numbers for 2014 and 2018 are unbelievably low. (Raleigh simply did not have a total of 112 violent crimes in 2018.)

The FBI’s homicide count (21) for 2020 doesn’t match the RPD’s year-end report (28). The rape and aggravated assault numbers are off, to, though not quite as significantly. I’ve asked RPD to explain the discrepancy but haven’t heard back. But you make do with what you’ve got.

Assuming the FBI’s data are correct, Raleigh reported 1,891 violent crimes last year, of which it cleared 397, or 21%—less than half the national average.

Caveat: Not all crimes are cleared in the same year they occur—you can’t expect a murder that takes place on Dec. 31 to get wrapped up before the ball drops—so it’s helpful to go back a few years. Because Durham’s data are wonky (see above), that’s difficult.

But in 2019, it reported 1,468 violent crimes, of which it cleared 126, or 8.6%.

Add the two years together: Raleigh has a violent crime clearance rate of 15.6%.

Once again, the national rate is 45.5%, and the average for similar-size cities is 35.1%.

Getting into specific crimes:

The FBI says Raleigh reported 21 homicides, of which it cleared 11. (Again, Raleigh’s year-end report said the city had 27 homicide incidents with 28 victims, and I’m inclined to believe the latter number is correct.)

That’s 52.4%, assuming the numbers are correct—they’re probably not—which still lags the national rate but is better than the rate for similar-size cities.

RPD’s rape numbers are hideous: In 2019, it cleared five of 192 rapes, and in 2020, it cleared 20 of 165. That’s a 7% clearance rate over the last two years.

Robbery is only marginally better: It cleared 53 of 408 in 2019 and 107 of 468 in 2020, a clearance rate of 18.3%.

Then there’s aggravated assault: 21% in 2020, 6.5% (!) in 2019.

This leaves us two possibilities: Either the data the RPD provided to the FBI are bad, or Raleigh officers are bad at solving violent crimes. (Their property crime numbers are poor, too.)

Over to Durham, where the crime-solving story isn’t much happier. This is violent crime:

In 2020, DPD solved 23.2% of reported violent crimes; in 2019, 28%. Those numbers are below the national average and the average rate for similar-size cities.

Homicide:

2018: 33 (reported), 19 (cleared), 57.6% clearance

2019: 37, 18, 48.6% clearance

2020: 36, 12, 33.3% clearance

3-year total: 46.2% clearance

Rape:

2018: 82, 38, 46.3% clearance

2019: 121, 12, 9.9% clearance

2020: 125, 19, 15.2% clearance

3-year total: 21% clearance

Robbery:

2018: 723, 215, 29.7% clearance

2019: 627, 139, 22.2% clearance

2020: 626, 135, 21.6% clearance

3-year total: 24.7% clearance

Aggravated assault:

2018: 1,125, 396, 35.2% clearance

2019: 1,262, 404, 32% clearance

2020: 1,660, 402, 24.2% clearance

3-year total: 29.7% clearance

I haven’t done enough reporting to know why things are the way they are—whether we can chalk this up to idiosyncrasies in the data or the cities or whether there are fundamental problems in police priorities or resource allocation. But the raw data are worth considering.

If you have any ideas for how I should interpret these numbers or turn them into a story, here is my encrypted email.

2. Durham DA Won’t Seek Death for Faith Hedgepeth’s Alleged Killer

One thing that’s always bothered me about capital punishment is its random application.

If Miguel Enrique Salguero-Olivares had been charged with murdering college student Faith Hedgepeth 15 years ago, a capital case would have almost been a certainty. If this had happened in certain parts of Texas or Florida, lethal injection would be a foregone conclusion. Even if he’d been charged in Wake County, there’s a decent chance Lorrin Freeman would have pursued a death sentence.

But it’s 2021 in Durham, and Satana Deberry is the district attorney. So Salguero-Olivares doesn’t have to worry about that. (Not that he’d really have to worry about that, since North Carolina hasn’t executed anyone in 15 years, and won’t execute anyone anytime soon. But that’s for another day.)

The Durham County District Attorney’s Office does not plan to pursue the death penalty against the man charged with killing UNC-Chapel Hill student Faith Hedgepeth. … The notice isn’t necessarily surprising. Deberry was elected on a platform of criminal justice reform, which included opposition to the death penalty. (N&O)

3. Alamance Confederate Monument Lawsuit Moves Forward

Last week, Superior Court Judge Kevin M. Bridges rejected Alamance County’s motion to dismiss a lawsuit brought by the NAACP, Down Home NC, Engage Alamance, and several county residents calling for the removal or relocation of the Confederate monument in front of the county courthouse.

The lawsuit argues, among other things, that the lawsuit—and the money the county spends to protect it—misuses public funds, violates the state constitution’s “equal protection and anti-race discrimination provisions,” and violates the state constitution’s “provisions prohibiting secession and mandating allegiance to the United States.”

Judge Bridges also rejected Alamance’s request to stay the litigation or transfer the case to a three-judge panel.

In a press release, Paynter Law, one of the firms representing the plaintiffs, wrote:

The monument stands illegally because the Constitution outlaws government action that sows disunion, denies equal protection, exhibits racial discrimination, and squanders public money. In 2020, the Alamance County Sherriff’s Office reported expending at least $747,672 on protests, a significant portion of which was used to address protests around the Confederate monument.

“The court’s ruling is a groundbreaking recognition of plaintiffs' claims that the Alamance County Confederate Monument has always been at odds with the values enshrined in our state’s Constitution,” says attorney for the Plaintiffs Gagan Gupta of Paynter Law. “The Monument’s location outside a prominent courthouse represents messages of racial disunity and secession that are unacceptable to an ever-growing portion of our citizenry.”