The Post-Roe North Carolina

Wed., Dec. 2: Women’s rights are on the ballot now + the Board of Governors isn’t happy about its upcoming move

» What Will a Post-Roe North Carolina Look Like?

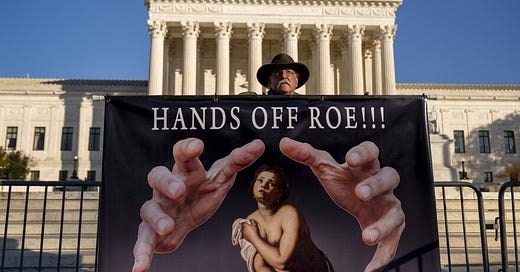

Yesterday, the U.S. Supreme Court heard arguments over Mississippi’s frontal assault on abortion rights. Mississippi passed a law banning abortion after 15 weeks of pregnancy, about two months before fetal viability, to challenge the newly ultraconservative Court to overturn Roe v. Wade and Casey v. Planned Parenthood.

I’m loath to make predictions. But based on what I heard, I wouldn’t bet on the constitutional right to abortion surviving intact. At minimum, the Court seems likely to eliminate the fetal viability threshold established in Casey.

If the Court reverses or weakens Roe, 21 states have laws on the books to immediately impose total or near-total bans on abortion, and at least five other states would almost certainly ban or severely restrict abortion soon after.

Those states include the entirety of what you might call the Extended Deep South—Florida, Georgia, Alabama, South Carolina, Mississippi, Tennessee, Louisiana, Arkansas, Texas, Kentucky, Oklahoma, West Virginia—except for Virginia and North Carolina.

The question: If the Court explicitly or effectively overturns abortion rights, what will that mean for North Carolina?

Before we get there, let’s look at the state of abortion currently. In 2019, 23,495 North Carolina residents had abortions, according to the Department of Health and Human Services. Here’s what we know about them:

» Age

< 14: 0.2%

15-19: 8.1%

20-24: 27.5%

25-29: 29.1%

30-34: 18.6%

35+: 13.1%

Unknown: 3.3%

» Race

White: 30.9%

Black: 45.6%

Indigenous: 1.1%

Other: 3.5%

Multi-race: 3.7%

Hispanic: 13.1%

Unknown: 2.3%

» Weeks of Gestation

< 8: 65.8%

9-12: 20.3%

13-15: 5.2%

16-20: 3.3%

20+: 0.2%

Unknown: 5.3%

Six hundred and twenty North Carolina residents obtained abortions in another state women. But a lot more women, it seems, come to North Carolina to receive abortions.

According to the Guttmacher Institute, North Carolina providers performed 29,500 abortions in 2017. If that’s correct, and if DHHS is also correct that 22,543 North Carolina residents received abortions in-state that year, that means that nearly 7,000 nonstate residents got an abortion in North Carolina, accounting for nearly a quarter of the state’s total.

I’m not sure what to make of that: The large student population? Easier access?

Guttmacher estimates that if surrounding states ban abortion, as many as 11.2 million women a year may drive to North Carolina to obtain the procedure—unless, of course, North Carolina joins its neighbors.

In that case, North Carolina women will have to drive several hours to Roanoke or Richmond, Virginia, to obtain abortions.

Since taking power a decade ago, North Carolina Republicans have enacted a number of restrictions on abortion access. Though they’ve passed nothing approaching an outright ban, they have managed to make obtaining an abortion more onerous, usually under the pretext of concern for the woman’s safety.

In 2017, 26 facilities—14 of which were clinics—provided abortions in North Carolina, down from 37 facilities (and 16 clinics) in 2014. Today, the National Abortion Federation lists 15 abortion providers in the state, including five in the Triangle.

Here’s what the state’s rules look like now, according to Guttmacher:

In North Carolina, the following restrictions on abortion were in effect as of January 1, 2021:

A patient must receive state-directed counseling that includes information designed to discourage the patient from having an abortion, and then wait 72 hours before the procedure is provided.

Health plans offered in the state’s health exchange under the Affordable Care Act can only cover abortion in cases of life endangerment, or in cases of rape or incest.

Abortion is covered in insurance policies for public employees only in cases of life endangerment, rape or incest.

The use of telemedicine to administer medication abortion is prohibited.

The parent of a minor must consent before an abortion is provided.

Public funding is available for abortion only in cases of life endangerment, rape or incest.

A patient must undergo an ultrasound before obtaining an abortion.

An abortion may be performed at or after viability only in cases of life endangerment or severely compromised health.

The state prohibits abortions performed for the purpose of sex selection.

The state requires abortion clinics to meet unnecessary and burdensome standards related to their physical plant, equipment and staffing.

(Read more about the restrictions here, and about North Carolina’s history of abortion laws here.)

The Supreme Court’s ruling won’t affect any of that. But it likely will affect a law North Carolina has had in place since 1973 that makes it a crime to perform an abortion after 20 weeks of pregnancy except in a medical emergency.

As it stands, that law is unconstitutional because it bans abortion before fetal viability.

Despite that, in 2015, Republicans passed a law narrowing the medical emergencies exempted from the 20-week ban.

When abortion providers sued, the state argued that it wasn’t enforcing the law. (In 2015, Gov. Pat McCrory signed a law requiring abortion providers to send the state an ultrasound image of fetuses aborted after the 16th week of pregnancy to determine whether providers were following the law the state said it was not enforcing.)

Federal courts didn’t buy it. In June, a federal appeals court barred the state from enforcing the 20-week prohibition.

If the Supreme Court eliminates the fetal viability threshold, however, that injunction goes out the window, and nothing will stop the state from prosecuting abortion providers who violate the 20-week ban. (Nothing, that is, except for district attorneys who refuse to take such cases to court.)

But only a tiny fraction of abortions take place after 20 weeks, and most of those involve medical emergencies. So the 20-week ban would affect, at most, a handful of cases a year. The real question is how far the General Assembly wants to push. After all, with Roe out of the way, social conservatives’ only impediment is Gov. Roy Cooper.

That means:

The 2024 governor’s race—probably between Lt. Gov. Mark Robinson, an unapologetic culture warrior, and Attorney General Josh Stein—will likely determine the right to choose in North Carolina. Unless …

Republicans first win legislative supermajorities next year (very possible) and wrangle enough votes on antiabortion legislation to overcome Cooper’s vetoes (more difficult).

Tl;dr: The future of abortion rights in North Carolina probably depends on:

a) Cooper living another three years (and not leaving the state long enough for Mark Robinson to act in his absence), and

b) Democrats retaining the Executive Mansion in 2024, and

c) Antiabortion Republicans never winning veto-proof legislative majorities.

The first one? Sure. The second? Even money.

But all three?

» QUOTE OF THE DAY

“Will this institution survive the stench that this creates in the public perception that the Constitution and its reading are just political acts?” —Justice Sonia Sotomayor

» BOG Mad That NCGA Didn’t Consult Them on Raleigh Move

The Assembly and the N&O dropped versions of this story at exactly the same time on Tuesday night/Wednesday morning. Read the N&O’s for the gist, The Assembly’s for the gory details, and my summary for the quick and dirty.

Basically, the General Assembly’s budget requires the UNC System to relocate from Chapel Hill to Raleigh next year, the latest piece of Republicans’ animus toward Chapel Hill and a likely forerunner to a merger with the community college system. But no one asked the Board of Governors—almost all of whom are Republicans, and some of whom are former lawmakers—for their opinions.

Some don’t think it’s a good idea. But they’re really pissed about being in the dark.

N&O:

The decision to relocate the headquarters out without the board’s input reveals the political power that lawmakers have over North Carolina’s higher education system. And it comes at a time when many faculty and staff members at the state’s flagship university in Chapel Hill have joined forces to push back against what they call “partisan interference.”

“The Board of Governors were set up as a buffer to make sure we keep, as much as possible, the politics out of the university,” [Leo] Daughtry said in an interview.

If you move the system and BOG headquarters to Raleigh, it would be “almost impossible” to do that, he said.

The Assembly:

Randy Ramsey has earned a reputation for running the UNC System Board of Governors with a strong hand, focused on calm, public unity in his role as chair. But under the surface, tensions are growing.

In a Monday email to Ramsey, Board of Governors member Art Pope made that friction explicit.

“I am dismayed to learn that as Chairman of the UNC Board of Governors, you knew in advance of the state budget Appropriations Act special provision to require the UNC System Offices to relocate to downtown Raleigh ... and never informed or brought this issue before the UNC Board of Governors for study, discussion, a vote or other action.”

That email, part of a flurry of back and forth between three dissenting Board of Governors members and System leadership, illustrates both frustration at policy and process, as well as revealing lessons on how power is wielded within the UNC System. …

Pope, along with board member and former state House Majority Leader Leo Daughtry and board member and former state Rep. John Fraley, strongly protested the exclusion of the Board of Governors in the decision to move the UNC System’s headquarters to Raleigh, which is estimated to cost up to $100 million. …

Ramsey, in a prior, emailed response, told the dissenting board members that he had spoken to Senator Berger and “it was clear he had no intention of changing direction on this decision.”