Welcome to the Jungle (Primary)

Tues., Nov. 9: Nida Allam runs for Congress + Mike Woodard probably will, too + what the Community Safety Department will actually do

+3 TOP STORIES

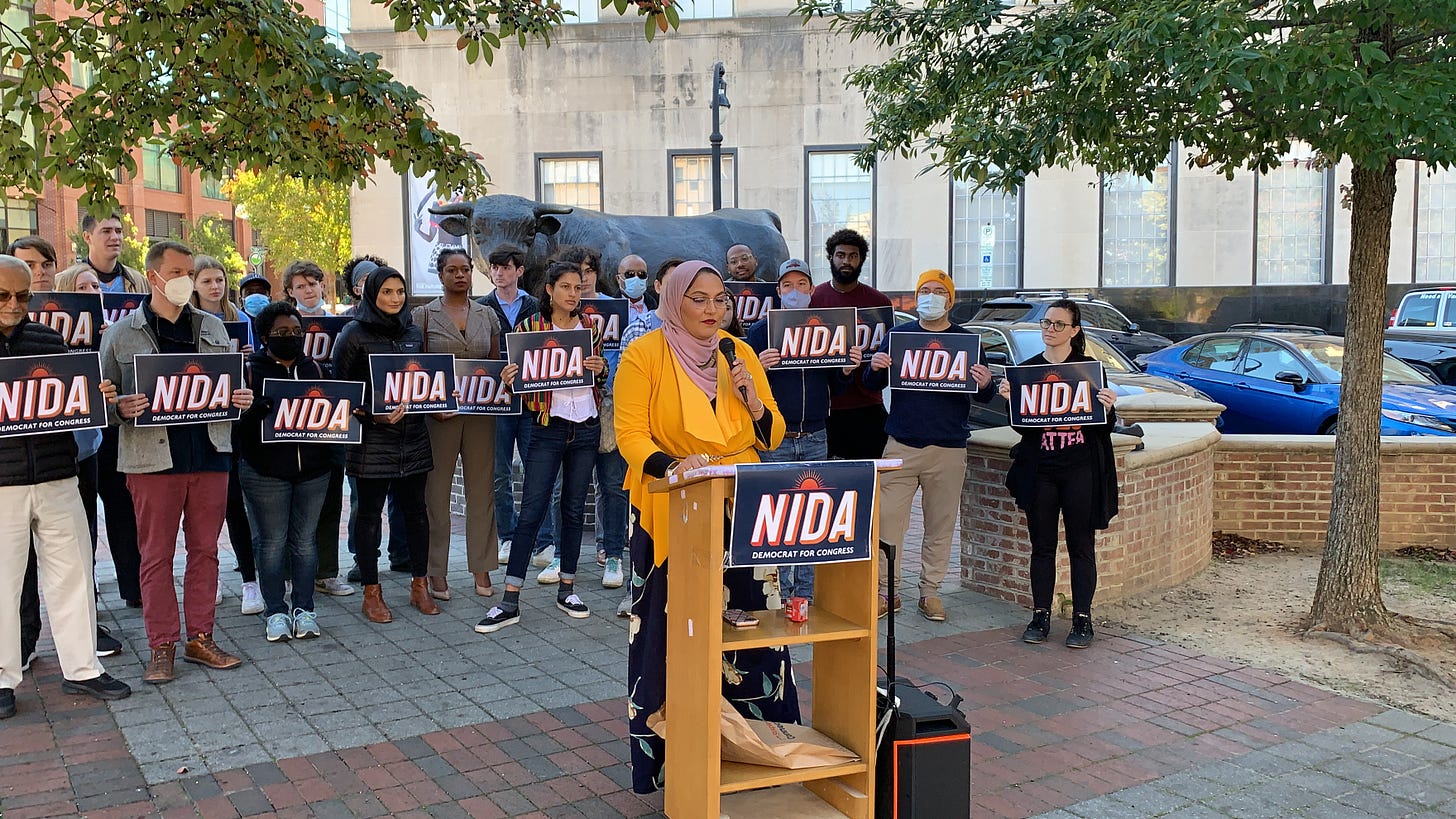

1. Durham Commissioner Nida Allam Runs for Congress

Nida Allam’s campaign manager, Maya Handa, told me on Saturday (under embargo, as they promised the launch story to the N&O) that the Durham County commissioner would announce her congressional bid yesterday, but Allam’s intention to run wasn’t a secret before that.

Watch Allam’s announcement speech here.

Though she’s been in office less than a year, she’s seen as a rising star among North Carolina Democrats, she has ties to the Bernie wing of the party (and the fundraising that comes with it), and, most of all, she has a narrative: Her friends were gunned down in a hate crime. She became an activist, then the first Muslim woman elected in North Carolina.

She would be the first Pakistani-American elected to Congress and, I believe, the first Muslim elected to federal office in the South. At 27, I think she would also be the youngest member of Congress, replacing one-man humiliation machine Madison Cawthorn.

Eight hours after it was posted on Twitter, her announcement video had been viewed 157,000 times. She got shout-outs from Mark Ruffalo, Nina Turner, Ilhan Omar, and Keith Ellison (and those are just the bold-faced lefty names I saw).

The other announced candidate, state Sen. Wiley Nickel, told the N&O that he raised more than $250,000 in anticipation of longtime U.S. Rep. David Price’s retirement. As of about 5 p.m., Allam said she had raised $55,000 in one day. (An hour later, she told me she was up to $60,000.)

Nickel announced his campaign within hours of Price announcing his retirement, which struck me (and not just me) as a) poor form and b) bad politics. Nickel’s announcement got lost in the stories heralding Price’s decades in office. Allam owned the news cycle.

Then again, two months from now, will anyone remember?

The way the district has been drawn, Nickel faces a disadvantage. While it dips into western Wake County—where his district sits—and heads out west to Orange County, its power center lies in Durham, and Allam isn’t the only pol with their eyes on the prize.

Whoever wins this primary will likely have the seat for as long as they want it.

2. Mike Woodard “Seriously Considering” Run, Too

State Sen. Mike Woodard, a former Durham City Council member, told me in an email last night that he is “seriously considering” a run. He’s put together a campaign team and plans to file with the FEC on Wednesday, he says.

He won’t be the last candidate. A quick roll call from the rumor mill:

Former Sen. Floyd McKissick Jr., a former city council member and longtime legislator who is now on the Utilities Commission; he’s also the son and namesake of a famed civil rights leader.

State Sen. Valerie Foushee, who has repped Orange County for two decades.

Former DCCC executive director and Duke adjunct Allison Jaslow.

Those are just the names I’ve heard.

If they all get in, that will be SIX candidates with name recognition and/or access to money.

With enough well-funded, viable candidates, the race could easily become a crapshoot. The winner might only need 30% (the state’s threshold to avoid a primary runoff) in March.

Allam wants to occupy the progressive lane, hoping that will be enough to separate her from the pack.

On that note: Maya Handa, Allam’s campaign manager, was most recently in Buffalo working for mayoral candidate India Walton, the democratic socialist who upset incumbent Byron Brown in the Democratic primary, then lost when Brown ran a write-in campaign in the general last week.

Tl;dr: Handa has experience winning Dem primaries from the left.

While it’s fair to say Allam is on Woodard’s left, Woodard has well-established progressive bona fides, and a lot of Durham progressives have supported him for a long time.

At the risk of oversimplifying, maybe think of Woodard as coming from the Durham People’s Alliance wing of the city’s progressive movement, and Allam as coming from the Durham for All camp.

Allam had a good workshopped answer for the inevitable youth-and-inexperience question—“The median age in this district is 36 …”—but Woodard has represented Durham since Allam was in grade school; in other words, he has a record to point to.

How much that will matter is anyone’s guess.

During her launch announcement, Allam touted her connections to Bernie and used the phrases “Green New Deal” and “Medicare for All.”

But she also said she would have voted for the infrastructure bill that passed the House this weekend over the objections of some Squad members, who didn’t want it decoupled from the reconciliation bill.

Punny headline aside, North Carolina doesn’t really have jungle primaries. Strictly speaking, jungle primaries are nonpartisan free-for-alls like California has. North Carolina has semi-closed primaries, which means that Democrats and unaffiliated voters will be able to vote in March.

2. What Durham’s Community Safety Department Will Actually Do

Yesterday, I promised deeper dives into aspects of Durham’s police reform debate that didn’t make it into my story on the subject. I’ll start today by getting into more detail about the Community Safety Department, specifically the two pilot programs it plans to roll out early next year. (As I was reporting the story, I was surprised by how many people—even politically engaged people—seemed in the dark.)

The department launched on July 1 with one employee—director Ryan Smith, formerly of the city’s Innovation Team—and a $4 million budget. Smith’s job, in essence, was to hire its first 15 employees and chart its future.

The RTI study of 911 calls led the city to create three overarching goals for the agency’s first year:

Run pilot programs that test policing alternatives

Work with the Community Safety and Wellness Task Force to develop new public safety initiatives

Manage several public safety-related contracts and agreements, including the violence interrupters program Bull City United.

The first of those is probably the most important—and would be the justification for transferring police positions to the new department.

As the story mentioned, Smith’s team plans to roll out two pilots: crisis call diversion and mobile crisis response.

The former is “informed by models currently operating in Houston, Austin, and Charleston,” Smith told me. In short, a mental health clinician embeds in a 911 call center to remotely assist with calls that deal with behavioral health crises.

The latter is based on programs in Denver, San Francisco, Albuquerque, Atlanta, and Eugene. All of these programs are similar—civilians deal with non-emergency 911 calls and behavioral health crises rather than cops—but they’re not identical.

The original is CAHOOTS, or Crisis Assistance Helping Out in the Streets, which began in Eugene, Ore., in 1989. Two-person teams of social workers and medics respond to 911 calls involving behavioral health crises. Of the 24,000 calls CAHOOTS responded to in 2019, only 311 required police backup, according to a Vera Institute case study.

Many cities have spun off their own variations.

Among CAHOOTS’ progeny: Denver’s Support Team Assisted Response, or STAR, which started last year. Its teams perform welfare checks and respond to reports of trespassing, public intoxication, and indecent exposure, among other things. In its first six months, STAR responded to 748 calls and never needed police assistance.

Other programs focus on individuals experiencing crises in public or take community referrals through a non-emergency number such as 311.

Two important things:

One fear that tends to arise with these programs is that unarmed civilians will be out of their depth and at risk when they encounter dangerous situations. The data suggest that isn’t the case.

The scope of the work varies. In some cities, it’s specific to mental health; in others, the responders handle loitering and public nuisance issues, too. That’s part of what the Community Safety Department is figuring out.

The other part is the geographic boundaries and hours of operation of the pilot program, both right away and as it expands. It won’t start 24/7, and it won’t cover the whole city. They need to pick neighborhoods and gather information; they plan to start small and slow expand, in consultation with first responders and behavioral health providers.

As of mid-October, Smith had hired six of the department’s 15 allotted positions. He plans to hire three more in-house; the rest will be contracted for the pilot programs.

He told me: “We’ve been learning a lot from other cities across the country, and there is some interesting variation in the make-up of alternative response teams. The city plans to use the pilots to evaluate what kinds of personnel are most essential in meeting the needs of residents experiencing certain kinds of mental health and quality of life crises, which is why we plan to contract out for these roles during our pilot.”

He (understandably) declined to comment on the city’s election or the debate over the transfer of up to 15 additional police vacancies, which will come before the new city council in December.

My original plan was to report on the first year of the Community Safety Department and then write about it. (I still plan to.) I thought Durham’s approach to police transformation was at once ambitious and carefully plotted, and people inside City Hall can’t say enough great things about Ryan Smith.

The election slapped a question mark not so much on the department’s existence but on how much support it will have going forward.

The “progressive” side (all things being relative) wants it to eventually reach something close to parity with the DPD. The “police-friendly” side views the department as augmenting the police.

I’ll dig into the incoming council’s views more tomorrow.