What I Learned by Reading 506 Submissions to Mark Robinson’s Indoctrination Task Force

PRIMER special report: Robinson will release his school-indoctrination report today. Here’s what you need to know before he does.

Note: I’ve been meaning to publish this story for a couple of weeks now, though I kept getting distracted by other assignments. To be honest, my schedule hasn’t permitted me to give PRIMER the attention it deserves lately, for which I apologize. But this week, I should be able to catch up on my to-do list. (What’s that they say about men planning and God laughing?)

In the meantime, this piece took a lot of reporting, so please share it to your various Twitters and Facebooks.

On July 14, North Carolina’s lieutenant governor, Mark Robinson, promised a legislative committee that his task force would soon release a report showing that teachers are indoctrinating students with liberal dogma and critical race theory “all over the state, unfortunately.”

Today—six weeks later—he’ll release the “Indoctrination in North Carolina Public Education Report” at a press conference with Senate leader Phil Berger and Superintendent Catherine Truitt. But the conclusion was never in doubt. Robinson said as much when he announced the task force in March: “People say, ‘Well, where’s the proof?’ Where’s the proof?’ We’re going to bring you the proof,” he told reporters.

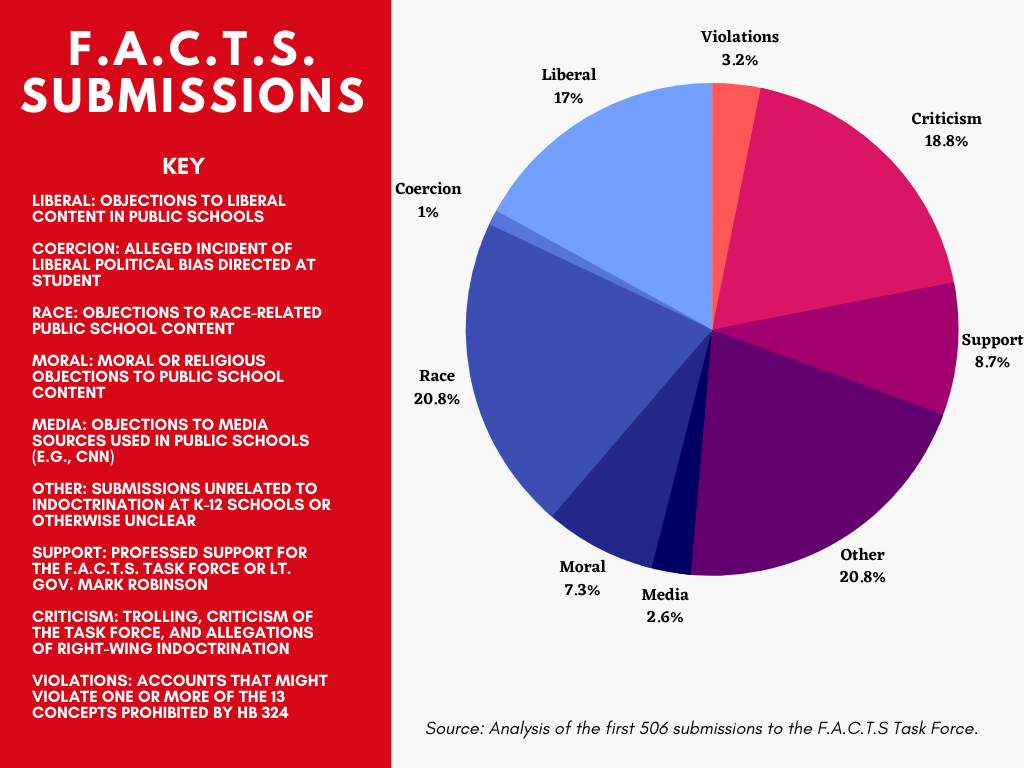

But the 506 submissions F.A.C.T.S. Task Force collected from the public through July 14, obtained through public records requests, provide little evidence of indoctrination, according to my review and analysis.

Only 21 submissions allege possible violations of the state Senate’s proposal to ban the promotion of critical race theory or describe incidents in which students were allegedly compelled to profess political beliefs, a standard of indoctrination established by the Supreme Court in 1943.

“[Robinson’s] whole starting point is, ‘There’s widespread indoctrination of our children. It’s rampant, and somebody needs to do something about it, and I’m that somebody,’” Justin Parmenter, a language arts teacher at Charlotte’s Waddell Language Academy and public education advocate, told me. “I think it’s pretty clear from all 500 of those submissions that that’s not going on.”

Brian LiVecchi, Robinson’s general counsel, told me on Friday that the task force takes a broader view of “indoctrination.”

“At the end of the day, what is ‘indoctrination’ other than an attempt by a person in a position of authority to influence or persuade a captive or subordinate audience to uncritically adopt a particular belief?” he said. “Especially when the authority figure has control over outcomes that are critical to the audience, those attempts to ‘influence’ can become coercive, whether intentionally or subliminally.”

Regardless, the submissions offer a unique window into what many conservatives are concerned about in public school classrooms. Critical race theory is only part of it—along with gender identity, socialism, and anything else considered “woke” or “progressive.”

Republican lawmakers are listening. Eight legislatures and three state school boards have banned critical race theory from public schools. After protesters demonstrated at school board meetings across North Carolina, Berger listened, too.

“Children must learn about our state’s racial past and all of its ugliness, including the cruelty of slavery to the 1898 Wilmington massacre to Jim Crow,” Berger said at a press conference in July announcing his support for House Bill 324. “But students must not be forced to adopt an ideology that is separate and distinct from history; an ideology that attacks ‘the very foundations of the liberal order,’ and that promotes ‘present discrimination’—so long as it’s against the right people—as ‘antiracist.’”

The General Assembly, he said, would pass legislation to “prohibit indoctrinating students while preserving the inviolable principle of freedom of speech.”

But unlike other states’ anti-CRT initiatives, HB 324 has no penalty or enforcement mechanism. Critics say it’s not serious legislation so much as an attempt to gin up the conservative base by appealing to racial anxiety.

Whatever the intent, it’s likely to be politically potent.

“Fear is a great motivator,” says Christopher A. Cooper, a political science professor at Western Carolina University. “We’ve always had fights over race. We’ve always had fights over how we emphasize the past. We’ve got this nationalized political environment. Put them all together, and you’ve got fertile ground for the fight.”

If critical race theory wasn’t the culture war’s hottest front when Mark Robinson took office in January, it was well on its way.

A combative Black Republican who rose to prominence with a viral gun rights speech—and whose campaign survived revelations about his anti-Semitic and anti-LGBTQ Facebook posts—Robinson quickly used his seat on the State Board of Education to disclaim systemic racism and denounce new culturally responsive social-studies standards.

After the standards cleared the Democrat-controlled board, Robinson announced the F.A.C.T.S. task force on March 16. It appears to have met just once—informally, Robinson’s office told me, and in secret, an apparent violation of the state’s Open Meetings Law.

By seeking allegations of ideological as well as race-related indoctrination from the public, Robinson cast a wide net. He received a wide array of responses.

Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools taught “very young children all about homosexuality and the transgenders,” one person wrote. A man said that three years of public schooling turned his daughter into a “full-blown socialist.” A mother reported that hearing Black children speak about their experiences with discrimination upset her daughter. A parent was bothered by a teacher including his pronouns in his email signature.

Thirteen people objected primarily to the “biased” media sources teachers used to discuss current events—usually CNN. Thirty-seven raised moral or religious objections to school content or policies, most often LGBTQ-related. For example, a middle-school counselor said that “as a Christian,” a policy prohibiting her from outing a transgender teenager to their parents “puts me in direct conflict with my religion.”

Scores complained about mask mandates or praised the task force. Nearly a hundred people mocked or trolled Robinson.

About 17% of the submissions accused schools of promoting liberalism, some blaming teachers for offering their political opinions or exposing students to ideas with which their parents didn’t agree.

Just five incidents alleged that students were forced to make or agree with political statements. For example: a quiz asking what type of people Republicans are, the correct answer being “rich white men”; a vocabulary assignment that included the sentence, “Donald Trump is a xenophobe.”

But several submissions that didn’t reach the “compelled speech” threshold nonetheless described questionable behavior, including one teacher who called a conservative high-schooler a “possible school shooter,” and another who opined that “all Christians are idiots.” (Worth noting: None of the submissions were verified.)

“I tell parents, ‘You are not entitled to never be pissed off, and you're entitled to agree with everything that’s taught,” Sloan Rachmuth, a conservative journalist and the president of Education First Alliance, told me. “‘Sometimes people are teaching things you don't agree with, and guess what? That’s okay.’”

The problem, she says, comes when children are discouraged from challenging controversial ideas.

“I've seen that a lot,” she told me. “Censorship is a problem. Compelled speech, it happens more often than you would think. I can tell you how it manifests: If children are taking a test and are compelled to say that there are more than two genders.”

But the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders—the guidebook used by psychiatrists—recognizes more than two gender identities, and many scientists view gender as a social construct distinct from sex, I pointed out. If a test question about gender constitutes indoctrination because it runs counter to some religious beliefs, why, I asked, wouldn’t test questions about evolution do the same?

“I think that we can jump into our sides and put on our jerseys, left and right, and kind of argue that out,” Rachmuth responded. “But if we really want to solve it, do we need to have a line in the sand, or do we need to be able to talk more and have more transparency and more discussion about where that line is?”

Rachmuth says Education First Alliance has its own confidential reporting system. “I mean, we have kids, literally, they have to implicate themselves,” she told me. “They have to actually sign a statement saying that they are a white supremacist.”

Nothing like that appeared in the submissions to Robinson’s task force that I reviewed.

The day after Robinson announced the F.A.C.T.S. Task Force, Republican lawmakers introduced HB 324, the Ensuring Dignity and Nondiscrimination in Schools Act. On May 12, the state House passed it on a party-line vote.

Without Democratic support, Republicans don’t have the votes to override Cooper’s veto. The Senate ignored the bill for two months. But in mid-July, Berger revived it alongside a proposed constitutional amendment to ban affirmative action.

Like most other states’ anti-CRT bills, the Senate’s rewrite of HB 324 doesn’t use the words “critical race theory.” Instead, it bars schools from “promoting” 13 concepts (see below), many of which are cribbed from an executive order Trump issued last September (since revoked) and obliquely reference ideas such as structural racism and white privilege.

Importantly, the bill defines “promote” as “to compel” students, teachers, or administrators to “affirm or profess belief” in a prohibited concept. Most of the task force’s 121 race-focused submissions don’t meet that standard.

Instead, parents complained about things like diversity surveys, lessons on whiteness in science, Black Lives Matter decorations in classrooms, and reading assignments (in particular, Ibram X. Kendi’s Stamped from the Beginning: The Definitive History of Racist Ideas in America and Angie Thomas’ The Hate U Give).

“Everyone knows how bad slavery was, but hearing about it for months now is getting old,” a Caswell County parent wrote. “I don’t hear any of these teachers talking about Hitler and how he tried to take out a whole race of people! Nor have I heard this teacher once say that Blacks in Africa were the ones selling others into slavery.”

A Currituck County parent was upset their child learned about Ruby Bridges. “My kid was so young, she didn’t comprehend why everyone was so mean to her in school. It’s too young to start race-baiting in elementary school.”

Only 16 submissions might qualify as promoting a prohibited concept, including high school homerooms that taught social justice lessons; a student-run club that gave classroom presentations on white privilege; and equity-focused teacher training and antiracist policies in the Charlotte-Mecklenburg, Pitt, Guilford, Wake, Gates, and New Hanover County school systems.

Berger’s office declined to comment for this story. But last month, when Capitol Tonight host Tim Boyum asked the Senate leader for examples of North Carolina schools using CRT, he responded, “I don’t know that the theory itself is overtly being used. But we have examples of folks really promoting teaching in the theory.”

Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools employs the term “antiracist,” he continued. And Durham’s city council approved a racial equity task force report that said education systems were designed to “indoctrinate all students with the internalized belief that the white race is superior.”

Berger might have also mentioned Wake County Public Schools, the state’s largest school district, which drew conservatives’ ire after adopting an equity policy that targeted systemic racism and holding a training conference that included sessions on “whiteness” and “microaggressions.”

Debates over how to understand—and teach—America’s racial history usually assume a familiar form, says William Sturkey, a UNC-Chapel Hill professor who specializes in the history of race in the South.

“It’s always been part of the conservative mantra, especially in the South, to downplay the disadvantages that Blacks have faced in the region,” Sturkey told me. “[Critical race theory] is just a new version of that.”

He points out that Berger linked his critical race theory bill with an amendment to ban affirmative action. The latter, Sturkey says, “is obviously a longstanding conservative dream to, after 300 years of racial inequality, just hit a reset button and enjoy all of the advantages that white people get at that current moment and say, ‘Oh, we’re all even now.’”

(Like HB 324, the amendment has long odds; getting it on next year’s ballot requires a supermajority in the General Assembly.)

The two are connected: African Americans have shorter life expectancies, are more likely to end up in prison, and have just 10% of the median net worth of whites. Antiracism proponents say these disparities are due to centuries of discrimination hardwired into the country’s institutions, and race-neutral solutions won’t fix them.

Indeed, in the half-century after Congress passed the Civil Rights Act, “no progress [was] made in reducing income and wealth inequalities between Black and white households,” according to research in the Journal of Political Economy.

To Berger, an ideology that says equality is insufficient can’t be reconciled with the meritocratic ideal of equal opportunity. (Among HB 324’s prohibited concepts: Meritocracy is inherently racist or sexist.)

That was also a common theme among the submissions to Robinson’s task force. Many writers dismissed the notion that people of color faced disadvantages.

One Mecklenburg County father noted that his daughter’s magnet school had a Black Lives Matter mural.

“First off, I am wondering why a public, tax-funded school is able to engage in politics, especially with young children,” he wrote. “Second, my daughter has asked why her life does not matter and others' lives do. It's a hard thing to explain. What else can I say to her besides the truth—society today only believes certain peoples’ lives matter, based on skin color alone, and that she is not eligible?”

While opposing critical race theory, Berger has also stressed that he doesn’t want to censor speech with which he disagrees.

“We don’t burn books with radical ideas; we read them, discuss them, and either accept or reject the ideas they present,” he said last month.

So the Senate bill tries to walk a tightrope, allowing “impartial” lessons on the prohibited concepts so long as they’re not “promoted.” (Administrators can contract with speakers, consultants, or diversity trainers who discuss the concepts under the same condition.) But again, that line is subjective, and the bill doesn’t say who determines when it’s crossed. Nor does it address how allegations will be investigated or what the penalty is for breaking the law.

In Tennessee, by contrast, if the state education commissioner determines a school has violated the critical race theory law, he or she can pull funding from the school.

Critics say the bill is not only toothless but redundant. Indoctrination is already illegal.

“The idea of compelling speech by students in and of itself is already a constitutional violation,” says state Senator Jay Chaudhuri of Wake County, the Democratic whip.

Students who are compelled by schools to profess beliefs can make their case in court.

“I would contend generally that a student or his/her parent(s) should not be placed in the position of filing a lawsuit against the public school they pay for because that school is breaking the law,” LiVecchi told me in an email, “and the better public policy position would be to prevent such occurrences on the front end if possible. I believe that is what the legislation is intended to do.”

But HB 324 wouldn’t do that in any tangible way.

The only tangible thing it does is require schools to notify the Department of Public Instruction and post lesson plans and contracts related to critical race theory at least 30 days in advance. Rachmuth thinks this is key.

“I've often wondered if the controversial aspect of it is the lack of transparency,” she told me. “And I’ve often wondered if exposing all of this to sunlight would take the mystique out of it and would stop the arguing.”

Cooper, the WCU professor, says Republicans’ goal is to send a political message—to its base and white swing voters—not pass a law. So the details of the legislation didn’t really matter.

“I’ve said throughout this [legislation] session, we are spending a lot of collective energy debating bills that have zero chance of becoming law,” Cooper says. “I mean, you know this is all a scrimmage game, right?”

Democrats agree. “I really believe that the issue of critical race theory is a politically fabricated issue to mobilize the Republican base for the 2022 and ’24 election,” Chaudhuri told me. “The new normal of the General Assembly seems to be that we’re making public policy assumptions without any evidence or facts.”

But what are scrimmages if not warm-ups for the real battle to come? Though HB 324 faces an uphill climb this year, if Republicans win supermajorities next November—after redistricting, a strong possibility—both it and Berger’s affirmative-action amendment will be back.

So, too, might a renewed push to expand school choice—a priority for Robinson, who is planning to run for governor in 2024, as well as Berger, arguably the state’s most powerful elected official—with allegations of indoctrination at the tip of the spear. (Berger has already suggested the Senate will hold hearings into Robinson’s report; his appearance at today’s press conference indicates that he wants to elevate its profile.)

Indeed, to at least some who wrote to the task force, the cure for public-school indoctrination is a state-financed private education.

As one parent from Henderson County put it: “School Choice. Unfortunately, that is the only answer. These wacko liberals running our schools know that normal people do not have a choice where to send their schools. We can homeschool, but that's not practical (or helpful) for most parents and kids. WE NEED SCHOOL CHOICE IN NC!”

The 13 Concepts

Public school units shall not promote that:

1. One race or sex is inherently superior to another race or sex.

2. An individual, solely by virtue of his or her race or sex, is inherently racist, sexist, or oppressive.

3. An individual should be discriminated against or receive adverse treatment solely or partly because of his or her race or sex.

4. An individual's moral character is necessarily determined by his or her race or sex.

5. An individual, solely by virtue of his or her race or sex, bears responsibility for actions committed in the past by other members of the same race or sex.

6. Any individual, solely by virtue of his or her race or sex, should feel discomfort, guilt, anguish, or any other form of psychological distress.

7. A meritocracy is inherently racist or sexist.

8. The United States was created by members of a particular race or sex for the purpose of oppressing members of another race or sex.

9. The United States government should be violently overthrown.

10. Particular character traits, values, moral or ethical codes, privileges, or beliefs should be ascribed to a race or sex, or to an individual because of the individual's race or sex.

11. The rule of law does not exist, but instead is a series of power relationships and struggles among racial or other groups.

12. All Americans are not created equal and are not endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights, including life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.

13. Governments should deny to any person within the government's jurisdiction the equal protection of the law.

Source: Senate Committee Substitute, HB 324.

Tomorrow, I’ll post synopses of the 21 submissions that allege indoctrination. I’ve run out of room to do so today.